Wednesday, May 31, 2006

No More Electoral College?

The two counter arguments from the article:

"Small states suffer here," said Assemblyman Michael Villines (R-Clovis). "Yes, California is a big state. But I don't want a candidate to go to 10, 12 big urban centers, win a majority and walk away with the presidency."

I don't understand why it is socially preferable to discriminate against voters in cities. Why should urbanites preferences for the holder of a national office count for less than residents of rural areas? What benefits justify these costs? Sure, small states lose in this change, but large states lose under the current system. Why would we think that the gains to the small states outweigh the losses to the large states?

"Direct democracies were properly seen by the founding fathers as very unstable because 50% plus one of the people can vote themselves anything and run roughshod over the rights of the minority, run roughshod over rule of law," DeVore said. "That is what the Electoral College is all about."

The founders were rightfully concerned about the dangers of direct democracy, but that's is why they wrote the bill of rights -- which is far more important for the protection against tyranny of the majority than the electoral college.

Seriously, how does a move toward direct presidential election raise the danger of tyrannical majorities? I am curious if the move to direct election of Senators met similar arguments. Do we think that was bad? I am asking. I've never really thought about it.

Information Asymmetry Solved

4 GWU students (Tony Moniello, Jay Jentz, Philipp Waclawiczek, and Jason Linden -- all are conveniently on the facebook) were willing to reveal to the Washington Post that they were the "player" type for a fairly pointless article on "wingmen." Should you encounter these fools do not believe that they've "written a few books", that they are lawyers, or that they "own all the Ben and Jerry's in the Northeast." Know that they are players and proceed accordingly.

Anyhow, for readers of "The Game", what does it say about the wingman? Do those guys use them or do they tend to fly solo?

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Hmm?

So much for outward appearances. What about the less obvious cues of attraction? Fascinating work on genetics and mate preferences has shown that each of us will be attracted to people who possess a particular set of genes, known as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which plays a critical role in the ability to fight pathogens. Mates with dissimilar MHC genes produce healthier offspring with broad immune systems. And the evidence shows that we are inclined to choose people who suit us in this way: couples tend to be less similar in their MHC than if they had been paired randomly.

How do people who differ in their MHC find each other? This isn't fully understood, but we know that smell is an important cue. People appear to literally sniff out their mates. In studies, people tend to rate the scent of T-shirts worn by others with dissimilar MHC as most attractive. This is what sexual "chemistry" is all about.

The message here is: trust your instincts -- except that there is an alarming exception. For women taking hormone contraceptives, the reverse is true: they prefer men whose MHC genes are similar to their own. Thus, women on the pill risk choosing a mate who is not genetically suitable (best to smell him first and go on the pill afterwards). This is a prime example of how chemical attraction can depend on your circumstances.

This last finding raises several interesting questions: Do women find thier existing partners less attractive when the go on/off the pill? Does this make them more likely to break-up/divorce during these periods? How are the children of women who met their partners while taking the pill different from other children? Does any of this create a natural experiment we can use to identify some interesting causal relationship.

Nice

The role of public intellectuals is less to come up with good ideas, which is fiendishly hard, but more to serve as a watchdog to get rid of bad ideas and prevent their coming back. There are more bad ideas and more purveyors of bad ideas than their benign counterparts. And the asymmetry is further compounded because, in Yeats's words, "The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity."I think the internet only increases the volume of bad ideas. Fortunately, a number of smart people have (frequently with no compensation) decided to become public intellectuals. Although, I am not sure if we are, on net, better off.

People don't want to live near sex offenders

We combine data from the housing market with data from the North Carolina Sex Offender Registry to estimate how individuals value living in close proximity to a convicted criminal. We use the exact location of these offenders to exploit variation in the threat of crime within small homogenous groupings of homes, and we use the timing of sex offenders’ arrivals to control for baseline property values in the area. We find statistically and economically significant negative effects of sex offenders’ locations that are extremely localized. Houses within a one-tenth mile area around the home of a sex offender fall by four percent on average (about $5,500) while those further away show no decline. These results suggest that individuals have a significant distaste for living in close proximity to a known sex offender. Using data on crimes committed by sexual offenders against neighbors, we estimate costs to victims of sexual offenses under the assumptions that all of the decline in property value is due to increased crime risk and that neighbors’ perceptions of risk are in line with objective data. We estimate victimization costs of over $1 million—far in excess of estimates taken from the criminal justice literature. However, we cannot reject the alternative hypotheses that individuals overestimate the risk posed by offenders or view living near an offender as having costs exclusive of crime risk.

Ticket Prices, Part 1

This suggests that something else is going on. Tony V. argues that under-pricing concerts may make sense as part of a long term strategy to maintain ties between the artist and their fans. This is on the right track, but I think it is more correct to simply state that ticket prices are affected by social influences.

Under-pricing tickets is only an issue for superstars. According to Krueger, only one-third of concerts sell out. So we are only interested in why superstar artists chose excess demand and potentially lower revenue when pricing their concerts.

As I have discussed previously, I believe superstardom does not depend exclusively on talent. Rather, I think Adler (1985, 2005) is basically correct – stardom arises because people desire a common culture. This article (discussed previously) shows that individuals choosing songs by unknown artists without social influences (i.e., making choices based only on their private assessments of quality) make very different choices from individuals making choices while aware of other's choices. While not perfect (e.g., this finding may not exist in the "real world" because people have more time and resources to devote to assessing quality), this study suggests that Adler’s basic premise is correct.

Adler’s argument relies on a premise similar to the one Gary Becker discusses in “A Note on Restaurant Pricing” (1991). Becker argues that individual demand for some goods (usually with some social component) increases with aggregate demand for that good. One way to think of Becker’s argument is that each person has some private willingness to purchase a good (in this case a concert ticket). This is what the person would be willing to pay if they had to enjoy the good without knowing if anyone else consumed the good. Private willingness to pay is then augmented by a willingness to pay for social goods. This is how much the person is willing to pay in order to consume goods and services that others consume (or that others want to consume). The simplest example of this phenomenon is the willingness to spend more on goods consumed jointly with friends (e.g., I will not go to expensive restaurants or full price movies by myself, but I will eat at cheap restaurants or attend matinees by myself). This principle also applies to goods not consumed directly with one's peers. People are willing to pay more for goods that people in their (existing or expected) social circle demand because they enjoy talking about their experiences with the good and because this consumption choice helps them to fit in and/or confirm their identity in certain groups. Further, as demand increases within my groups, these effects become stronger, and my willingness to pay for the good increases. If this social effect is strong enough, Becker shows that demand curves can be upward sloping.

Becker’s model provides one potential reason for low ticket prices. Firms can only raise prices as long as the positive effect of aggregate demand on my demand outweighs the negative effect of higher prices. Setting prices too high is dangerous because once a few people decide that the price is too high and that they aren’t going to consume the product the whole thing can unravel. These individuals’ unwillingness to purchase lowers the marginal utility of purchase for these people’s friends, and now they don’t want to buy at the high price. And so on until the firm reaches a “low price” equilibrium (closer to the one determined by the “private willingness to pay”).

Thus, two things constrain the concert pricing decision. First, many consumers don’t know their social willingness to pay until after the concert is sold out. Once buyers know that they will share an experience with lots of others and that many others will be jealous that they got to attend, their willingness to pay to attend increases. Current concert sales arrangements prevent artists and promoters from extracting these rents. Instead, they accrue to scalpers and to ticket brokers (and now, with internet sales opportunities, to some fans).

Second, as we discussed in class, markets which rely on this sort of social coordination to maintain high prices are very fragile. The high prices are frequently not justified by differences in the quality of the product. Instead, they reflect arbitrary coordination in consumer tastes. As such, producers have limited ability to maintain their market advantage. They simply have to hope that they remain popular (and invest a lot in marketing/publicity, etc which might help them maintain their popularity). This may constrain artists’ attempts to extract more rents out of their fans. They may be aware that perceived “gouging” of their fans might cause fans to seek out a competitor group and their popularity to evaporate. Thus, they try and avoid going anywhere close to the point where this resentment might grow within any substantial sub-group of their fan base.

This gets us started, but I think there are still some questions which I hope to return to in later posts: How does concert pricing interact with other merchandise (e.g., CD) sales in market with strong social influences? How does the fact that promoters typically had to decide on a price in advance (because tickets for a tour tend to go on sale simultaneously) affect pricing? Do promoters set prices lower then they might otherwise in order to avoid risk? What has changed to allow promoters to raise prices so substantially in recent years? Have some artists more secure in their popularity than they used to be? How much has concert demand increased because the internet more clearly points to what is popular and allows people to enjoy greater social returns to their experiences in on-line communities? Do higher concert prices reflect artists trying to make-up for revenue lost to file sharing? (Probably not, my guess is that, if anything, file sharing just increases demand for concerts.)

Sunday, May 28, 2006

Learn Math

orless numerate students tended to rate a student's exam performance as better on a 7-point scale if they were told she had answered 74 per cent of items correctly in her exam, than if they were told she had answered 26 per cent incorrectly. By contrast, more numerate students were less affected by the way such information was presented. (Numeracy was tested with 11 maths questions on probability).

students were given the chance to win cash if they picked a red bean from a jar. Less numerate students were more likely than numerate students (33 per cent vs. 5 per cent, respectively) to choose to take their chances with a jar that had 9 red beans out of 100, than with a jar that had 1 red bean among 10, probably because they were swayed by the sight of more red beans in the first case, even though the odds were poorer.

I am curious how much susceptibility to framing affects individual productivity in different occupations and how much the returns to math/economics degrees is related to this?

Saturday, May 27, 2006

Correlation is Not Causation

Homer: Not a bear in sight. The "Bear Patrol" is working like a

charm!

Lisa: That's specious reasoning, Dad.

Homer: [uncomprehendingly] Thanks, honey.

Lisa: By your logic, I could claim that this rock keeps tigers away.

Homer: Hmm. How does it work?

Lisa: It doesn't work; it's just a stupid rock!

Homer: Uh-huh.

Lisa: But I don't see any tigers around, do you?

Homer: (pause) Lisa, I want to buy your rock.

Friday, May 26, 2006

Hear, Hear ...

We also discuss other things, such as teaching ability. But about 90 percent of the weight in hiring goes to research, only about 10 percent to teaching. Not once have I heard anyone ask, "How well equipped is this candidate to help college students sort out their lives?" If I ever posed such a question in a faculty meeting, my colleagues would think I was joking.

...

I am open to the idea that we should take a broader view in promotion and hiring than we do. I would increase the weight given to teaching relative to research. I would give some weight to life experiences outside of academia, such as working in policy jobs, writing op-eds, writing books for nonspecialists, and so on. But my perspective is a minority view in my department and, I believe, in research universities more generally.

I've long agreed with Greg's position. I also don't see why the Harvard economics department doesn't take advantage of the gains from specialization and hire a few teaching/mentoring specialists. Each year there are between 200-350 economics concentrators. Senior surveys indicate essentially none of them will graduate satisfied with the degree of faculty contact. Given the current faculty composition, this doesn't surprise me at all. People who do great research are best at mentoring people like themselves who want to and are capable of producing great research. This occurs because these are the students that the faculty actively pursue, but also because these are the students the faculty actually have the knowledge to help (i.e., many faculty have no experience outside the academy and as such can offer very little advice on any non-academic topics -- this lowers the expected productivity of faculty-student relationships and likely leads both parties to try and avoid them).

Ultimately, this means that very top students can obtain pretty good mentoring here, but the median studentis unlikely to develop much of a relationship with faculty. I doubt that marginal changes in the weight assigned to teaching in the hiring process will change that. So I don't see why the department just doesn't bring in a handful of the best teachers/mentors and set up institutions (e.g., weekly lunches and assigning them to large lectures) that make sure that these profs get to know most every economics concentrator. I think hiring such specialists would increase the productivity of the department in at least 5 ways:

1) it would improve the average quality of instruction in courses (particularly large lectures)

2) these specialists could serve as default mentors, letter of recommendation writers, and thesis advisors for students who struggle to get noticed (particularly in their first few years when they are stuck in large classes) -- given the number of letters of recommendation I've written as a lowly TF, I've long wondered how many students don't apply for internships, grants, etc. because they don't feel comfortable asking any faculty for a letter of recommendation.

3) their ability to serve as default advisors would also free up other faculty to do more research or provide better advising to their advisees by reducing the number "marginal" students they feel obligated to advise (and by teaching classes it may be very costly for them to teach).

4) also, I think these faculty could serve to improve the matching of faculty and student by facilitating introductions and matching students and faculty who are likely to form a productive pairing.

5) they allow the department to hire people with greater background diversity to better match the interests of the students and better match supply with demand.

I'm sure there are more reasons, but its been awhile since I thought about the particulars of my plan (I came up with it 3 or 4 years ago).

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Here's a surprise ...

The basic idea was to solicit thousands of predictions from hundreds of experts about the fates of dozens of countries, and then score the predictions for accuracy. We find that the media not only fail to weed out bad ideas, but that they often favor bad ideas, especially when the truth is too messy to be packaged neatly.

The evidence falls into two categories. First, as the skeptics warned, when hordes of pundits are jostling for the limelight, many are tempted to claim that they know more than they do. Boom and doom pundits are the most reliable over-claimers.

Between 1985 and 2005, boomsters made 10-year forecasts that exaggerated the chances of big positive changes in both financial markets (e.g., a Dow Jones Industrial Average of 36,000) and world politics (e.g., tranquility in the Middle East and dynamic growth in sub-Saharan Africa). They assigned probabilities of 65% to rosy scenarios that materialized only 15% of the time. In the same period, doomsters performed even more poorly, exaggerating the chances of negative changes in all the same places where boomsters accentuated the positive, plus several more (I still await the impending disintegration of Canada, Nigeria, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Belgium, and Sudan). They assigned probabilities of 70% to bleak scenarios that materialized only 12% of the time.

Second, again as the skeptics warned, over-claimers rarely pay penalties for being wrong. Indeed, the media shower lavish attention on over-claimers while neglecting their humbler colleagues.

I am curious if, similar to what Glaeser argues with respect to beliefs, pundits do better and/or the media prefer "better" pundits for stories that are likely impose direct costs/benefits on their consumers.

(h/t Mark Thoma)

Think carefully about your first job

"Lost in the argument over whether young people today know how to work, however, is the mounting evidence produced by labor economists of just how important it is for current graduates to ignore the old-school advice of trying to get ahead by working one's way up the ladder. Instead, it seems, graduates should try to do exactly the thing the older generation bemoans — aim for the top.

The recent evidence shows quite clearly that in today's economy starting at the bottom is a recipe for being underpaid for a long time to come. Graduates' first jobs have an inordinate impact on their career path and their "future income stream," as economists refer to a person's earnings over a lifetime."

To test this effect, the authors look at several economic studies that use economic conditions upon graduation as an instrument. These studies find that students who graduate from business school during a recession have an average lower income than those who graduate during good economic times. Furthermore, these differences in wage stick around for well over a decade, indicating that a large part of future income is based on luck.

"The Stanford class of 1988, for example, entered the job market just after the market crash of 1987. Banks were not hiring, and so average wages for that class were lower than for the class of 1987 or for later classes that came out after the market recovered. Even a decade or more later, the class of 1988 was still earning significantly less. They missed the plum jobs right out of the gate and never recovered."

"These data confirm that people essentially cannot close the wage gap by working their way up the company hierarchy. While they may work their way up, the people who started above them do, too. They don't catch up. The recession graduates who actually do catch up tend to be the ones who forget about rising up the ladder and, instead, jump ship to other employers."

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Nike + Apple = Cool

Check it out

(h/t The Big Picture)

What's in a name? Take 2

The study's authors sent more than 1,100 identically worded e-mail inquiries to Los Angeles-area landlords asking about vacant apartments advertised online. The inquiries were signed randomly, with an equal number signed Patrick McDougall, Tyrell Jackson or Said Al-Rahman. The fictional McDougall received positive or encouraging replies from 89 percent of the landlords, while Al-Rahman was encouraged by 66 percent of the landlords.

Only 56 percent, however, responded positively to Jackson.

(h/t Mahalanobis)

Seriously ...

Seriously, I've watched it three times now (twice just now), and I really don't see how this supports Delay in any way. Am I missing something?

Good Idea

So, a PhD dissertation for an economist; calculate how much more we would have to spend on employing teachers now in order to attract the talent that used to go into teaching.

The idea motivating this question is that restrictions on female labor participation increased the average quality of workers in "female" occupations (like teaching or nursing). Reducing barriers to female employment allowed talented women to take higher paying jobs in other sectors. While real wages for teachers doubled between 1950 and 1990, I (and the author of the question above) wonder if this increase was enough to maintain average teacher quality (the author clearly believes that this wasn't enough)?

Update -- The Hanushek and Rifkin paper behind the link for the change in real teacher wages provides a rough sense of the problem in Table 6. In 1940, 52.5 percent of male college graduate non-teachers made less than the average male teacher, and 68.7 percent of female college graduates made less than the average female teacher. In 1990, the percentage of male and female college graduates making less than the average teacher had fallen to 36.5 and 45.3 percent respectively.

In Table 7, they present the results of an attempt to decompose the source of the change in teachers relative earnings into 4 groups -- pure wage changes, changes in the educational level of non-teachers, changes in the overall age distribution, and relative changes in the teacher's age distribution. Not surprisingly, most of the decline is attributed to pure wage declines.

To the extent that those who would otherwise be high quality teachers choose to take higher paying non-teaching jobs, these pure wage declines have likely lowered the average quality of teachers.

I further wonder how a potential decline in teacher quality interacts with the growth in school enrollment. A much higher proportion of the population stays in school now (i.e., the dropout rate is lower). Most of these additional students are (likely) from the bottom part of the ability distribution. Do we require higher or lower ability teachers to teach these students? If we are ok with teachers serving a babysitting function, then I guess this might be ok. Or if lower ability students still learn as much as they can from "lower quality" teachers. However, if lower quality students require even higher ability teachers, then this potential trend is of serious concern.

More -- This paper by Corcoran, Evans, and Schwab argues that while the average aptitude of female teachers did not decline much from 1957 to 1992, the propensity of those in the top of the distribution to become teachers declined dramatically. They state, "the likelihood that a female from the top of her high school class will eventually enter teaching has fallen dramatically from 1964 to 1992 by our estimation, from almost 20% to under 4%."

This paper by Caroline Hoxby and Andrew Leigh, however, argues wage compression that lowers the returns to teaching ability is more to blame than the growth of opportunities in other sectors. The abstract:

There are two main hypotheses for the decline in the aptitude of public school teachers since 1960: improved job opportunities for females in other occupations and the compression of teaching wages owing to unionization. Using data on several college graduating cohorts from 1961 to 1997, we investigate both hypotheses. To separate the hypotheses, we exploit the fact that states varied considerably in the progress of unionization and female wage parity. We proxy for a teacher's aptitude with the mean college aptitude of students at her undergraduate college. We identify the effects of unionization using laws that legalized and facilitated teachers' unionization. The evidence suggests that compression of teaching wages is responsible for about three-quarters of the decline in teacher aptitude. Females' opportunities in alternative occupations do matter, but opportunities improved rather similarly for females of all aptitudes. Although alternative occupations drew women out of teaching in general, they did not have a sufficiently disproportionate effect on high aptitude women to explain the bulk of the decline in teachers aptitude.

Change in the Ticket Market

Iraq

Answering that question requires first answering two other questions: where would we like to be and where are we now? That is, what are our objectives and how close are we to achieving them? Only after we address these questions should we address the question of how do we close the gap between where we are now and where we would like to be (i.e., what should we do now).

Currently, I am not sure I know what the objective is anymore (it keeps changing), nor do I have a really good sense about how close we are to achieving it. Heck, I can't even tell you with any degree of certainty whether or not we are getting closer to or moving further from achieving it. This probably explains why I don't have a strong opinion about what we should be doing now (well, that and the fact that I have very little incentive to invest the effort in formulating a detailed opinion).

As a reminder to those of you wishing to formulate or update your opinions here are the broad strokes of the economic approach. The broad objective, I guess, is to reduce or eliminate threats to America and American interests. (Of course, in order to assess the impact of policies on our pursuit of these objectives, we need to clearly define American interests, and in a global community it is not obvious how to best define them.) Deciding on a course of action requires that we assess the likelihood of ALL of the possible outcomes in Iraq and their affect on our interests, and that we understand how any policy we might choose changes the likelihood of different outcomes. This allows us to approximately define the expected benefits associated with different policy options which should then be weighed against the costs.

Middle eastern expert Juan Cole offers his (pessimistic) opinions about where we are headed here. His bottom line:

I am not optimistic. I think the likelihood is that either Iraq will descend into a Yugoslavia-type maelstrom with much death and destruction and a break-up into mini-states as a result; or it will descend into a Lebanon-type maelstrom with much death and destruction but manage to come back together as a weak nation-state in the end. The second is the better outcome for the region and the world, but it is not guaranteed. Both scenarios are dire, and could spin out of control into regional conflagration.

I am not sure if he's correct, but I was reading the interview and realized that I didn't even have the basic tools to assess his opinion. Thus, I decided to do a little blogging to kick start my brain a little bit. I would like to think that there is some way to avoid what he thinks is likely, but that may just be wishful thinking at this point. We may have passed the point of getting the parties in Iraq to find an arrangement which produces self-sustaining, mutually beneficial cooperation.

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

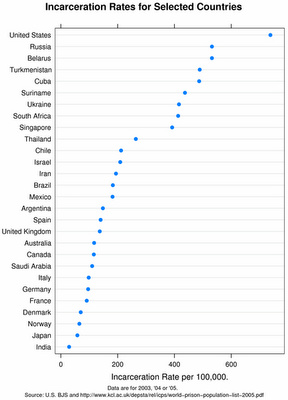

American Exceptionalism?

Something about this is very wrong (I'm not sure what). As is the fact that 12% of black males in their late 20s are incarcerated.

Symmetry Thesis

The symmetry thesis: A given person likes (loves) you as much as you like (love) him or her.

I have encountered many apparent refutations of the symmetry thesis, but with time most have turned out to be spurious. I find the symmetry thesis a surprisingly strong predictor of human behavior and inclination.

I have to say I don't get it. He seems to be suggesting that an exogenous increase in how much I like you will prompt a symmetric increase in how much you like me. Certainly, if I like you more I may be willing to do more to make sure you like me, but does this always occur? If I try, am I always successful? Does the relationship return to symmetry? Let's bust open our tool kit and see if we can figure this out.

Recall that how much I like/love you is a function of two things -- the total product of our relationship, how that product is allocated through negotiation/bargaining (and this is heavily affected by what I might expect from choosing the next best option). I ultimately like/love people who, relative to the other available options, provide me with the highest levels of utility. Typically, this involves matching with someone who you combine well with (i.e., you produce alot together) and with whom it is easy to divide the product of the relationship (i.e., there are low bargaining costs).

So let's assume that there is some random increase in how much person A likes person B. I can think of a variety of examples where this might happen, but when it happens do we observe a symmetric increase in B's feelings for A? I don't think this is necessarily true. A and B's ability to achieve symmetry depends on A's ability to get B to like him an equal amount. This requires that A know what to do to affect B's feelings toward him and have the resources to successfully do this. Neither of these things should be taken as given.

For instance, assume that A and B start in a symmetric relationship. Now, imagine a situation where A needs help and B provides it. How will this affect the relationship between A and B? It seems pretty clear that A's regard for B should increase, but it is not obvious that B's regard for A will move symmetrically. In one scenario, B enjoys giving what A required (i.e., providing this assistance is not a cost but a benefit). If the amount that B enjoys giving equals the amount the A appreciates receiving, then the relationship is all square. However, if the amount that B enjoys giving is less than how much A appreciated the help or if (as we expect to usually be the case) providing the assistance to A was actually costly to B, then A needs to "compensate" B in order to re-establish symmetry. Finally, there is the very weird case where the opportunity to help made B like A more than receiving the help increased A's fondness for B. In this case, A needs to actually insult B in some way to re-establish symmetry (this may be what happens in many abusive relationships).

Do we think that A and B will return to the symmetric position? Some might, but many will not because relationship prices are not clearly marked. The return to symmetry requires that A know what B expects in return and that A is able to provide this. If A asked for the favor thinking that it would "cost" less than Y but B agreed to it expecting to be compensated at greater than X (note that this process is further complicated by the fact that relationships frequently don't use tit for tat compensation but rather elaborate subtle exchanges over long periods of time), it is not hard to end up in a situation where Y is less than X. Now, instead of B liking A more, B is disappointed, upset, insulted and likes A less. (This might lead A to like B less, but I don’t think this is the path to symmetry Cowen had in mind.)

Further, in some cases, it is nearly impossible for A and B to achieve symmetry. Imagine that B saved A’s life. A may really like B, but A likely cannot ever transfer enough to B to provoke B to feel the same was toward A.

Ultimately, while how much A likes B is an important determinant of how much B likes A, I do not think that A liking B is sufficient for B to have reciprocal feelings toward A. B may provide A with lots of surplus, but there are still barriers to A’s ability to ensure that B feels the same way. Fixed aspects of A may prevent A from producing things that B values highly (e.g., B may want someone who looks a certain way or is of a certain ethnic or religious background). Similarly, A may face a binding resource constraint and may not be able to transfer any more of his relationship surplus to his partner because he cannot afford what his partner wants. Or, as in the case above, A may not be able to figure out the right mix of stuff to provide before B gives up on him.

Finally (on a slightly different note), it is possible that the local friendship/mate markets are skewed. Particularly in the mating market, if there are not equal numbers of available men and women of appropriate quality, we actually expect to observe asymmetric relationships. Those in short supply face strong outside options and, as such, should be able to extract more than their share of the relationship product. So, outside options also an affect relationship symmetry.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Al Gore -- Part II

First, on the front page of the "An Inconvenient Truth" website you'll notice that they have a tally of the number of people who've pledged to see the film opening weekend. This is a direct attempt to coordinate demand like we discussed in class. The goal is to get lots of people there to a) enhance their experience because they get to be part of the crowd (remember that individual demand for movies increases with aggregate demand), b) coordinate word of mouth advertising (that is, get lots of people talking about the movie at the same time so the message is reinforced), and c) hopefully generate enough box office to get more "free press" by getting in the news.

Also, on the front page are 2 great quotes. One, from Upton Sinclair highlights the point, discussed in the previous post, about the incentive to not believe things which are personally costly, "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on not understanding it." The other, from Mark Twain states, "It ain't what you don't know that gets you in trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so."

Second, it is common knowledge that Al Gore claimed to have invented the internet. The claim was the source of many late night jokes and much media criticism, and, as sad as it may be, may have lost Gore the election. Of course, Gore never stated that he invented the internet, but how his "absurd" claim came to be common knowledge and a key component of his image as "an exaggerator" is an interesting case study in social processes -- particularly information cascades (coupled with the realization that they are particularly prevalent in politics where individual incentives to "get things right" is low).

Gore told Wolf Blitzer in March of 1999:

But it will emerge from my dialogue with the American people. I've traveled to every part of this country during the last six years. During my service in the United States Congress, I took the initiative in creating the Internet. I took the initiative in moving forward a whole range of initiatives that have proven to be important to our country's economic growth and environmental protection, improvements in our educational system.

During a quarter century of public service, including most of it long before I came into my current job, I have worked to try to improve the quality of life in our country and in our world. And what I've seen during that experience is an emerging future that's very exciting, about which I'm very optimistic, and toward which I want to lead.

Essentially, a writer for Wired took a quote out of context and spun it like Gore claimed he was the founder of the internet. Various Republican operatives and media members repeated the story and its interpretation of Gore's statement -- Gore claimed to invent the internet. This led to comedians making fun of it, and (especially since it was 18 months before the election) most people accepted it as truth without bothering to investigate its truth (why would they?).

Anyhow, you can read a complete description of the story (including detailed description of Gore's work promoting the internet while in congress at this link.

Differences in Beliefs -- The Environment Edition

A Science magazine survey of all peer-reviewed studies on climate change showed that of the 928 independent studies done to date, (those not paid for by industry) all concluded that global warming is a real and growing threat.Global warming is exactly the type of issue that we expect markets to fail to solve. It combines two classic forms of market failure -- externalities and public goods, so it shouldn't surprise us that there is a problem. Nor is it all that surprising that people are slow to warm up to the scientific evidence saying there is a problem. Dealing with the problem may impose costs on me. So as long as there is someone out there telling me that the problem is not real (i.e., I don't have to incur costs), I am happy to believe them. The bigger the cost to me, the more skeptical of the evidence I will be.

There are no independent studies saying otherwise. Yet stories sampled from newspapers, television and magazines, show that 53 percent suggest global warming is unproven.

In that way, global warming is much like the evidence that tobacco caused lung cancer. For decades it was greeted by the industry, politicians, doctors paid to do ads and the media with unwarranted skepticism -- until everyone accepted that smoking makes you deathly ill.

If the costs to me associated with fixing the problem are likely very large (i.e., I am an industry), this simple model suggests that I should pursue two courses of action. First, I should fund "studies" which suggest that the problem is not real (i.e., the marginal benefits of policies to fix the "problem" are zero). Second, I should make sure lots of people think that policies to deal with this problem are extremely costly so that they are inclined to dismiss the evidence. E.g., you will lose your job and the economy will collapse if these policies are pursued (i.e., the marginal cost of fixing the non-existent problem is huge).

I grew up in the midst of one of the most contentious of these debates -- the spotted owl controversy. In the late-80s, environmentalists sued under the endangered species act to stop logging in the habitat of a threatened species -- the northern spotted owl. All of the elements discussed above were on full display throughout this period. First, loads of stories were produced suggesting that there were plenty of spotted owls and that happily lived outside of the old growth habitat that the environmentalists sought to protect. So the marginal benefit of protection was zero. Second, and much more prominent, were the scare tactics. Protection of the spotted owl was going to kill the economy of the Pacific Northwest. The dominant story was that this would touch off an economic collapse similar to the Great Depression.

Ultimately, the environmentalists won in large part because they hired very smart economists who were able to convince the judge that economic collapse was not eminent. The judge basically lifted the testimony of the plaintiffs expert, my past and future employer Ed Whitelaw, in his decision stating, "The timber industry no longer drives the Pacific Northwest's economy. Job losses in the wood-products industry will continue regardless of whether the northern spotted owl is protected. The argument that the mightiest economy on Earth cannot afford to preserve old-growth forests for a short time, while it reaches an overdue decision on how to manage them, is not convincing today." And this was right. The economy didn't collapse. Indeed, Oregon and Washington were two of the only states in the country to not experience the recession of the early 1990s.

The point, I guess, is that there are lots of incentives to ignore a problem like global warming and there are lots of people who will try and make it easy for your to do this because they stand to gain alot from this. Try and ignore the spin, use your brain, and inform yourself, and if every independent, peer-reviewed paper says this is a problem, you should probably at least pay the issue a little attention (like, go see the movie). (And yes, I am shamelessly attempting to employ social pressure to incentivize you to get involved in solving this public goods dilemma).

Sunday, May 21, 2006

Oh Man.

In the vein of sports economics, let me briefly describe some of the findings in Will Hauser's term paper on NBA referees. Using data for the complete 2005-2006 NBA regular season, Will shows that home teams, on average, do, in fact, have fewer fouls called on them while at home. The raw difference in mean fouls per game between the home and visiting teams is -1.15 fouls. This difference is roughly the same when examined in a regression with controls for day of season, point margin throughout the game (as measured by the score difference at the end of each quarter), and team and opponent fixed effects (i.e., the coefficient is identified by comparing the games the same teams play against each other home versus away).

There are two main explanations for this finding. First, officials have an incentive to slant their calls toward the home team because of social rewards (cheers)/punishments (boos) from the crowd. Second, teams/players perform differently at home versus the road (e.g., road teams are tired from traveling, and this causes them to foul more). Unfortunately, we cannot distinguish between these two explanations for the result (but since this is a course on social effects, the officials story is preferred).

So how important is one foul per game? Very conservative, back of the envelope calculations suggest that 1 foul translates into slightly more than 1 point per game. During the regular season 5% of games were won by a single point (and 7% of games went into overtime). Thus, a single point is not irrelevant. Will points out that in 2004-2005 the Cleveland Cavaliers missed the playoffs by 1 game after losing 3 games on the road by 1 point (but only 1 game at home by 1). Thus the home foul advantage might have kept the Cavs out of the playoffs last season.

Further, it is possible that officials also favor the home team on traveling, 3 seconds, and close out-of-bounds calls. If true, this would further increase teams' home court advantages.

When we started this project, the initial expectation was that officials would be more prone to crowd influence when the crowd was very intense (e.g., late in close games). However, the opposite result was found. Quarter by quarter analysis indicates that the home-road differential is largest in the first quarter and declines each quarter and is not significant in the fourth quarter (and non-existent in OT). Also, there is no home-road differential in games televised nationally on ABC. These two findings suggest that officials "raise their game" during big moments. In economic terms, they are likely aware that the NBA will pay more attention to blown calls at key moments, and the costs of punishment from their bosses probably outweighs the effect of the crowd.

Friday, May 19, 2006

Beliefs About Immigration

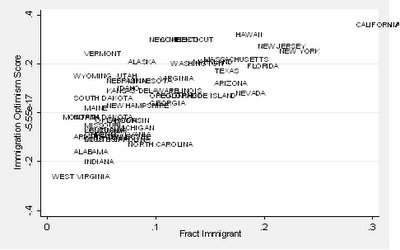

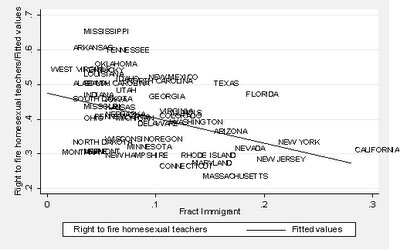

Figure 1

Caplan interprets his results to suggest, "that people who rarely see an immigrant can easily scapegoat them for everything wrong in the world. Personal experience doesn't get in the way of fantasy. But people who actually see immigrants have trouble escaping the fact that immigrants do hard, dirty jobs that few Americans want - at a realistic wage, anyway."

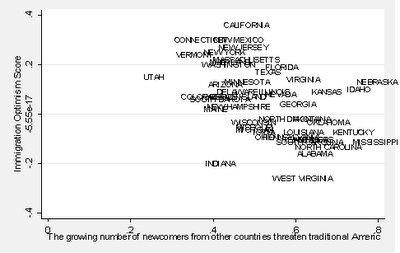

It should be noted, however, that people who fear immigrants taking American jobs also believe that immigrants threaten "traditional American values" (see Senate passing English as national language, uproar over a Spanish version of the national anthem, ...). Using the combined PEW Values Survey (1987-2003) and aggregating respondents by state, I document a strong correlation between the fraction of respondents who agree with the statement "newcomers from other countries threaten traditional American values" and the fraction that think immigrants "steal" American jobs in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The second figure suggests that one could modify Caplan's argument to say that people who interact with immigrants are also less likely to think that they threaten traditional American values.

I agree with much of this description. It is consistent with the findings of the roommates paper we discussed earlier (being randomly assigned to a roommate from a different background increases your sympathy toward that group). And with the story Ed Glaeser and I advocate in the "Myths and Realities" paper that interactions with immigrants in the marketplace (or factory) produced liberal cultural attitudes on the coasts.

However, I think it is important to note that other variables might drive the correlation. Caplan argues that their is a causal effect of exposure to immigrants on tolerance of them. While I think that there is reason to believe such an effect exists, I am not sure that the relationship is as strong as the above figures suggest.

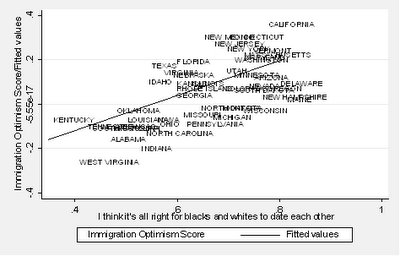

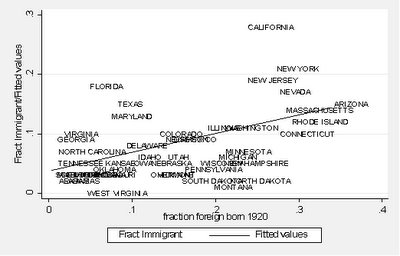

There are other explanations that could easily explain the observed relationship. E.g., immigrants may (randomly or rationally) choose to live in areas that are populated with people who are likely to tolerate them (or people who are predisposed to tolerate them might be more inclined to live near them). Indeed, there is a strong correlation between the immigration optimism score, the current fraction of the population that are immigrants, and other "liberal" attitudes towards minorities. Figures 3 and 4 show the strong correlation between the immigration optimism score and beliefs that it is ok for blacks and whites to date each other, and the correlation between the fraction immigrant and the belief that schools should have the right to fire homosexual teachers (data also from combined PEW Values Survey).

Figure 3

Figure 4

Further, immigrants tend to locate in places which have typically been attractive to immigrants (which as discussed in the Myths and Realities paper also correlates with liberal beliefs).

Figure 5

Thus, at least some of the observed relationship between current immigration and tolerance of immigrants is endogenous (or driven by omitted variables). Ultimately, more work needs to be done to deepen our understanding of the relationship between immigration, diversity, and tolerance. It seems clear that there is some sort of a relationship, but how big and how it operates needs more study. To better understand the causal effect of immigration on tolerance, I would be curious to see how views of immigrants, etc. changed after an immigration shock like the Mariel boat lift.

Thursday, May 18, 2006

MTV -- Your Source for Names

“Of the last couple of generations, Nevaeh is certainly the most remarkable phenomenon in baby names,” said Cleveland Kent Evans, president of the American Name Society and a professor of psychology at Bellevue University in Nebraska. ... The surge of Nevaeh can be traced to a single event: the appearance of a Christian rock star, Sonny Sandoval of P.O.D., on MTV in 2000 with his baby daughter, Nevaeh. “Heaven spelled backwards,” he said.

A few years back, my friend Dave Evans noticed a similar relationship between artists who are popular on MTV and the names given to newborns. Specifically, he found that names like Britney, Mariah, Aaliyah, and Selena all spiked in popularity at first album or singer death. I wonder how much of the increase is due to parents consciously naming their kids after pop starlets? If this effect is substantial, am I the only one who thinks that is weird?

Also, I like unique names. Until my name became semi-trendy, I liked the fact that it was unique (seems like that satisfies the purpose of a name -- a unique identifier). Sure it sucked that there were never pencils or mini-license plates, or whatever with my name on them in the stores, but overall I like being unique. Maybe this whole writing words backward is the way to find cool new names. For many years, I called my sister Nag'em (which is her name, Megan, backwards) because it seemed to fit her.

More Cheating

Tony wonders if this increase will lead away from reliance on honor codes and toward increased enforcement. This is one possibility, but I don't think it will happen. The problem is that at most schools enforcement is left to faculty, and, as discussed earlier, faculty don't particularly want to be bothered with this. So increasing the probability of catching cheaters seems difficult. Schools could also try and discourage cheating by increasing punishments, but I am not sure they have much room to increase them because they are already pretty severe.

Ultimately, I think the real trick is for faculty to adopt methods which make it harder to cheat. E.g., when I Tf'd 1011a, we designed the exams so that no calculators were necessary, so all students could have on their desks were the exam and a writing utensil. Further, they were primarily analytical exercises that cheat sheets or notes were unlikely to provide much assistance on. I think the only way to really deal with growth in cheating is to adjust teaching methods so that it is more difficult to use technology to cheat.

Perhaps, if schools want to address the problem they can invest in developing and disseminating other ideas which do this.

Revisiting the Fairy Tale

Growing up, I am certain all of you encountered, and perhaps embraced, the notion of fairy tale romance. This view posits the existence of some perfect mate who we are destined to meet and live with happily ever after.

That is, one can find love without costs. Somewhere out there a perfect match awaits us -- someone who is a far better match than any alternatives (i.e., the relationship product from pairing you with this person far exceeds the relationship product from any other possible pairing). Further, this person is so perfect that you will never have to engage in costly bargaining (because they have no traits you find annoying or vice versa and you agree completely on who should do what and how things should be allocated). Finally, you WILL meet this person (there are no search costs). You need only keep an eye out and overcome the few obstacles that stand in the way.

There is a reason we describe such romance as a fairy tale. Real love comes with a variety of costs -- search costs, forgone opportunities, bargaining costs. The importance we assign to these costs plays an enormous role in determining how we date and marry.

Some people believe strongly that a Mr. or Ms. Right exists and can be found with appropriate searching . Such people essentially assume that partnering with the "wrong" person imposes large costs because they forego the option of pairing with someone substantially better (more productive) and staying with the wrong person requires lots of extra bargaining and negotiation.

This approach to dating makes sense if one believes that people are very complicated and very hard to change. Under these assumptions, pairing with the "wrong" person substantially lowers an individual's welfare. As such, it makes sense to incur large search costs (date alot) in order to find the "ideal" mate. Further, we want to make dissolving imperfect matches fairly easy because resolving incompatibilities whenever they are found may be extremely costly.

The alternative view assumes people are relatively simple and capable of change. As such, relationship success hinges not on finding Mr. or Ms. Right, but rather it hinges on people having the right attitude and being able to figure out how to make things work. Under this view, searching wastes energy and awareness that someone better exists only makes it more difficult to come to terms with what is, in fact, a good relationship.

The extreme version of this approach is arranged marriage. In arranged marriages two relative strangers are paired off and essentially told to "make it work." Many do, although it is important to note that such success does not indicate that imperfect matches and bargaining costs are irrelevant. Indeed, such "make it work" approaches to relationships are typically accompanied by large barriers to divorce and strong gender norms which govern the relationship. This suggests that people need to be pushed in order to "make it work."

So which assumptions are correct? Which approach to dating produces the best outcome for individuals? for society?

I don't know. Part of me worries that people make themselves worse off by consistently worrying about if there might be someone better available, and worse, people quit otherwise successful relationships because they view it as cheap (don't have to incur bargaining costs and a better match exists). If people overestimate the cost of bargaining with their partner or their chances of finding someone substantially better, then people might be made better off in the long run if we made it more difficult for them to break-up. On the other hand, if most people don't make these mistakes regularly, then making it more difficult to break-up only forces many people to stay in bad relationships longer then is necessary (imposing a big loss on social welfare).

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

I Sill Don't Get It -- $1000 Khakis Edition

Some khaki pants are now selling for as much as $1055; $400 and $500 khaki pants are becoming common.

Last fall, I was wandering through SoHo with friends and we stumbled into Dolce & Gabbana. Did you know they have a children's section where you can spend $800 on a coat for your 4 year old?

It is pretty obvious that most of the benefits that are being enjoyed by these consumers is not related to their use of the actual good. That is, as long as it came with the right brand and marketing campaign, I could put just about any pair of khakis on the rack and people would still pay me the $1000.

I think this is weird. Essentially, in our system, we pay others (in the form of high prices) to create arbitrary differences in the social signals and emotions that are associated with certain products (or certain types of the same product). (Yet, as the ad post below points out, we have to be paid to watch the ads which are integral to creating many of these differences.)

And while I have argued that I think this is all pretty silly, the only reason we (as a society) should care is if this system somehow reduces social welfare. Ultimately, that is a tough debate. One the one hand, status goods serve as a carrot to motivate people to work. On the other hand, they also encourage people to steal and are associated with a variety of negative emotions (like envy). Further, the money spent on these goods is not lost. It is just transferred to other people. Jobs and wages are good. However, it is possible that this money could be spent in alternative ways (e.g., investing in capital or protecting African kids from malaria) which produce better jobs and wages or raise social welfare in some other significant way. Last, it is possible that most people would prefer this convention to go away, that we are in a bad equilibrium, and we'd be happy for someone to intervene and make it go away. One possible scenario is that, for whatever reason, there are a few people who care about this stuff and make their opinions known with vigor (a friend who is a professor at HBS related a story from one of her colleagues of a student criticizing a professor on a course evaluation for not wearing his pants "right"). Fear of offending these few leads many to follow along. Now, even though the vast majority of people don't care, it seems as though everyone cares. In this way, we get stuck in a bad equilibrium until enough people (or enough of those in "leadership" positions) coordinate to shift the norm (for a real example see the growth in the acceptance of business casual in the 90s).

Ultimately, I think there must be better ways to signal your identity and/or status to others. E.g., why not walk around with our net worth displayed on our cell phones, or, if we think that might over-encourage savings, why not display your total lifetime earnings up to that point? I like the total earnings thing -- it works as a signal because we could make it hard to fake, it encourages work, but consumption or saving are now totally up to you. And for those think this over emphasizes money, we could make the display color coded to match your emotional state (which we would measure daily using some hormone metric or a brain scan or something).

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Wrong By Association

"If someone is sufficiently evil everything about them and what they believe is wrong. Whether or not it's right."

So to summarize the logic: Person A is evil. Person A believes X. Therefore, regardless of other evidence and your prior beliefs, X is wrong (and anyone who believes X is evil).

(Colbert also discussed a topic from class, the growth segregation based on beliefs, during Monday's "Word".)

Ads

Advertising is simply media content that is complementary with consumption of the goods advertised: this just says in economic terminology that people who consume the ads are more likely to consume the products or, even more simply, that ads sell stuff.

...

What about consumers? An obvious case of the Becker-Murphy story arises when the ads tell a story that enhances the subjective value of consuming the good in question. A pair of shoes that make you feel like a basketball star is better (for the target market) than a pair of shoes that just covers your feet. Becker and Murphy pay a fair bit of attention to this case, and so do people who comment on them.

But this isn’t the only way that ads can be complementary. Ads that make you discontented with your existing possessions, or reduce the subjective value of competing products work just as well.

The economic model presented by Becker and Stigler provides a simple and elegant way of distinguishing the two. If advertising is a good, which enhances the package of ad+product, consumers will be willing to pay for it. If advertising is a bad, consumers will have to be paid (or forced) to consume it.

An immediate consequence is that most of what we think of as advertising is a bad. We watch TV ads not because we like them, but because we are paid with the programs they accompany. This is the point made by the TV executive who said we were breaking the contract if we watched the programs but not the ads (he did say we could take a break to go to the toilet, IIRC).

Given the public good properties of financing broadcast TV, it’s possible to make a second-best argument that this social arrangement improves welfare on balance (I still need to work through this one, but for me at least, the price is too high, and I hardly ever watch ad-inclusive TV).

Billboards, though, are an unmitigated bad. If we wanted to look at them, we would pay to go and see them as with movies and concerts. And given that we are selling our attention to advertisers on TV and radio, those who force billboards into our field of view are taking that attention without payment, just like telemarketers making collect calls.

An immediate policy conclusion, the exact obverse of the one about TV viewers watching ads, is that users of billboard advertising should be required to pay everyone who goes past. Given the transactions costs of implementing this, they should be taxed at rates comparable to the advertising charges of TV stations.

Protect the Press

1) Individuals start with a belief (their priors).

2) New information arrives.

3) The new information is evaluated (e.g., is it true, what might be wrong or misleading about it, etc.)

4) Prior beliefs are updated to reflect the new information (even if the new information is somewhat unreliable, priors should shift a little bit to reflect the greater (un)certainty that the new information suggested).

The media plays an important role in steps 2 and 3. Most of the information we receive on almost every topic is provided to us by the media. Journalists primary job is obtaining and conveying information of interest to their audience. To what extent journalists engage in step 3 and help their audience assess the quality or importance of new information is a source of great debate which I hope to return to in later posts.

Today, though, I want to focus on the important role the press plays in providing citizens with the information required to execute their primary role in our society -- providing government with their consent.

As a refresher for those of you who slept through civics or government class, I point out that in our system of government, within the rules of the constitution, the government acts on our behalf and, in theory, is supposed to do what "We" want it to. The power of government is not supposed to be used to achieve the goals of those we've entrusted to run it; it is supposed to be used to achieve to goals of "We, the people."

The role sourced to the media in this process is to provide us (or at least those of us who are interested) with the information necessary to decide what the government should be doing on our behalf -- what are the problems that need addressing; what are the ideas/policies that might be implemented to address these problems; what are the tradeoffs associated with these policies (although the media doesn't do a very good job with this aspect). We also rely on the media to inform us when the government (and/or various individuals within it) is engaging in behaviors that We might find objectionable.

In order to ensure that this process functions, the very first amendment to our Constitution granted all those who have information to share (particularly the press) the right to provide that information. Further, over the years, we have also decided, in order to obtain important information that otherwise might not be available, that members of the press should be allowed to withhold the identities of those who provide them with information in most cases.

We put this stuff first when writing the Bill of Rights because we cannot do our job as citizens -- provide our consent to be governed and decide who should be doing the governing -- unless we have the relevant information.

The current administration has decided that we don't need to know what is being done on our behalf. They believe that all we care about is that terrorists don't attack us, that we care only about the ends (no terrorist attacks) but not the means (torture, secret prisons, lack of due process, unprecedented domestic surveillance, ...).

Further, they seem to believe that the issue is not open for discussion. They vilify and are seeking to prosecute those who have leaked, reported on, or question their methods. Yesterday, the FBI confirmed that it has obtained reporters phone records without the reporters knowledge and without judicial consent. As a senior official stated, "It used to be very hard and complicated to do this, but it no longer is in the Bush administration." Georgia10 describes how the process used to work:

Judge Sweet ruled that indeed the phone records in that case were "protected by the qualified reporters' privilege for confidential sources, which exists pursuant to the First Amendment and federal common law." The government in that case was unable to overcome that privilege, so it could not have access to the phone records. You can read the Washington Post article about the decision here.

Now, of course, journalists were compelled to disclose their sources in the Plame investigation, where the court ruled that the government's interest outweighed whatever interest Miller and Cooper had in protecting their sources. However, as Judge Sweet pointed out, when it comes to phone records, all of a journalist's confidential sources, even those wholly unrelated to the investigation, can be exposed. Not to mention that the privacy of the individual reporter is implicated.

In any event, the fact remains that the protection of a reporter's phone records has been and should be within the purview of the judicial branch, where the government can set forth evidence as to why it requires access and reporters can counter with the implications of granting that access.

I strongly agree with that last paragraph. If the government wants this kind of information they need to convince a judge that it is necessary. As an economist, I understand incentives. When it is cheap and easy to do something (obtain reporters phone records), people will do it (and will likely abuse it). When it is costly, people will only do it when it is important. This process makes sense to me.

Ultimately, the marginal benefit from the infinitesimal reduction in the likelihood of terrorist attack that are associated with these leaks (and with these policies more generally) does not outweigh the loss of the higher costs of obtaining (and thus the reduced supply of) the information citizens require to execute their duties. (Or more simply, Benefits= 0, Costs>0 => Bad Idea.)

Monday, May 15, 2006

Eyebrows raised, mouth agape, and speechless

Dear Jorge plans to address the nation tonight, a speech wherein he will almost surely attempt to deceive citizens into believing that he does not wish the mass migration from Mexico to continue unabated.

...

And he will be lying, again, just as he lied when he said: "Massive deportation of the people here is unrealistic – it's just not going to work."

Not only will it work, but one can easily estimate how long it would take. If it took the Germans less than four years to rid themselves of 6 million Jews, many of whom spoke German and were fully integrated into German society, it couldn't possibly take more than eight years to deport 12 million illegal aliens, many of whom don't speak English and are not integrated into American society.

To read something more intelligent about immigration, see Tyler Cowen and Daniel Rothschild's LATimes op-ed.

NSA Phone Data

We all agreed that the lack of oversight or any clear rules governing the process is not cool. Further, even if it is somehow necessary for the government to keep the big database for efficiency reasons, we agreed that they shouldn't be able to access it without a warrant (keeping in mind that the FISA court can grant warrants ex post when necessary).

Update -- in case you are still in the group who thinks this stuff doesn't matter (f/ABC News):

A senior federal law enforcement official tells us the government is tracking the phone numbers we call in an effort to root out confidential sources.

"It's time for you to get some new cell phones, quick," the source told us in an in-person conversation.

We do not know how the government determined who we are calling, or whether our phone records were provided to the government as part of the recently-disclosed NSA collection of domestic phone calls.

Other sources have told us that phone calls and contacts by reporters for ABC News, along with the New York Times and the Washington Post, are being examined as part of a widespread CIA leak investigation.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

Stop dating! Just buy a playstation 3.

"Economists suggest lasting marriage produces as much happiness as an extra $100,000 a year in salary. This might sound like a strong case for getting hitched. But many economists have shown that happiness is expensive—$100,000 will buy you only a small amount of joy. Studies like these also hide individual variation. Marriage isn't worth $100,000 to just anybody. A recent German study found that matrimony's hedonic gains go disproportionately to couples who have similar education levels but a wide income gap. Worse yet, on average, people adapt very quickly and completely to marriage. As anyone who's ever consumed seven pumpkin pies in one sitting knows, we quickly get used to our favorite new things, and we just as quickly tire of them. As Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert artfully puts it, "Psychologists call this habituation, economists call it declining marginal utility, and the rest of us call it marriage."

"We submit that a relationship with a PlayStation 3 is worth at least $100,000 a year in happiness for all individuals. Unlike a nagging spouse, the PS3 doesn't care about your income or your level of education—it loves you just the way you are. It is true that you will eventually become accustomed to your sleek new PS3, but this will take an extremely long time. The PS3, after all, has been built expressly to keep mind-blowing novelty coming and coming and coming. Periodic infusions of novelty—new games—will keep the endorphins flowing."

The authors continue to explain how buying a playstation is one of the most rationale $500 investments that one could make.

While I find the author's comparison interesting, I don't necassarily agree that its fair to compare feelings of love to the mild amusement generated by a playstation...though Im sure many at Harvard have tried. Still, I know that my $149 investment in my PS2 has had immense returns.

Update from Bryce -- This may be the best post on this blog so far. Awesome. Just awesome.

Gains From Trade

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Women and Negotiation

Two experiments show that sex differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations may be explained by differential treatment of men and women when they attempt to negotiate. In Experiment 1, participants evaluated candidates who either accepted compensation offers without comment or attempted to negotiate higher compensation. Men only penalized female candidates for attempting to negotiate whereas women penalized both male and female candidates. Perceptions of niceness and demandingness mediated these effects. In Experiment 2, participants adopted candidates’ role in same scenario and assessed whether to accept the compensation offer or attempt to negotiate for more. Women were less likely than men to choose to negotiate when the evaluator was male, but not when the evaluator was female. This effect was mediated by women’s nervousness about negotiating with male evaluators. This work illuminates how differential treatment may influence the distribution of organizational resources through sex differences in the propensity to negotiate.

For more on this topic, you can see facts and discussion of her book "Women Don't Ask" (with Sara Laschever) at this website. A taste:

Women Don't Like to Negotiate

In surveys, 2.5 times more women than men said they feel "a great deal of apprehension" about negotiating.Men initiate negotiations about four times as often as women.

When asked to pick metaphors for the process of negotiating, men picked "winning a ballgame" and a "wrestling match," while women picked "going to the dentist."

Women will pay as much as $1,353 to avoid negotiating the price of a car, which may help explain why 63 percent of Saturn car buyers are women.

Women are more pessimistic about the how much is available when they do negotiate and so they typically ask for and get less when they do negotiate—on average, 30 percent less than men.20 percent of adult women (22 million people) say they never negotiate at all, even though they often recognize negotiation as

appropriate and even necessary.

Jerk-o-meter

Of course, if Pentland is right about the importance of social signaling, we might want to be more aware of our nonlinguistic behavior. Pentland says he has been looking into commercializing his research, and he already has a few ideas. One product that's currently in the works: the Elevator Rater, a program designed to assess your delivery of 60-second sales pitches and help you learn to sound more persuasive and charismatic. Another potential product is something Pentland calls the Jerk-o-Meter--it's a real-time speech analysis application that runs on your cell phone and will tell you when your voice is getting out of control.

The Power of Incentives -- Diebold Voting Machines Edition

The companies response:

"For there to be a problem here, you're basically assuming a premise where you have some evil and nefarious election officials who would sneak in and introduce a piece of software," he said. "I don't believe these evil elections people exist."

I agree with the company. No one has any incentive to try and steal an election. Why would anyone ever take the time to familiarize themselves with the computer code, get a position as an election official, and stick a USB drive into a voting machine they happen to be moving around? That's all so costly. What benefits could possibly outweigh these costs?

Thursday, May 11, 2006

If it is not illegal it should be

So real quick then, marginal benefit some tiny change in the likelihood of catching terrorists; marginal cost the cost of accumulating and analyzing the records and the loss of any expectation of privacy when using the phone for all American citizens (and any effects of this loss of the expectation of privacy). And don't underestimate the size of these costs. Right now you think, "I don't call anyone interesting", so who cares. Others, though, do care. People call all sorts of numbers which could, in the wrong hands, be used to embarrass them or get them in trouble (e.g., calls to psychiatrists, lawyers, reporters, ...). Further, it is easy to forget this because our country is relatively old and stable, but the time may still come when we need to be able to call each other in order to reclaim our individual sovereignty from an overzealous government.

Ultimately, if the government can convince a judge or someone that my phone records are important to providing public safety, fine I might be willing to pay this price. But I need to know that there are legitimate reasons for me to give up this expected privacy and that there are rules governing the use of these records and severe punishments for their miss use.

Missed Opportunity

Oh well.

More Beauty

Three things in the article stood out to me. First, psychologists have found that "moms of attractive first-born infants were more attentive and affectionate than moms of less attractive first-borns," that "attractiveness is significantly related to social acceptance and popularity for girls throughout the entire school year. For boys, low attractiveness is associated with rejection by peers. Moreover, the likelihood that unattractive boys would be rejected increased, not decreased, as the school year progressed and as the boys became better acquainted." (They imply that unattractiveness directly causes this effect, but it could be that unattractiveness is correlated with less friendly personalities (see lack of maternal attention above) and that is why this pattern is observed.)

Second, they show that infants respond to attractiveness. They show, "Babies look longer at adult-judged attractive faces than at unattractive faces, regardless of whether the face is male or female, white or black, adult or infant" and "The infants more frequently avoided the stranger when she was unattractive than when she was attractive, and they showed more negative emotion and distress in the unattractive than in the attractive condition. Furthermore, boys (but not girls) approached the female stranger more often in the attractive than in the unattractive condition, perhaps foreshadowing the types of interactions that may later occur at parties and other social situations when the boys are older!"

Finally, who is pretty? Well, people who look average. Not people who are average within the attractiveness distribution, but rather people whose faces resemble a composite of lots of faces.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

Bad Social Capital -- Crony Edition

One legitimate reason for the opposition to capitalism in Latin America is that it frequently has been "crony capitalism" as opposed to the competitive capitalism that produces desirable social outcomes. Crony capitalism is a system where companies with close connections to the government gain economic power not by competing better, but by using the government to get favored and protected positions. These favors include monopolies over telecommunications, exclusive licenses to import different goods, and other sizeable economic advantages. Some cronyism is found in all countries, but Mexico and other Latin countries have often taken the influence of political connections to extremes.

Throughout the term, I was a pretty strong advocate for social capital investment. However, social capital certainly can be employed to produce socially inefficient outcomes. Cronyism is probably the worst aspect of social capital (the other big potential drawback to social capital is getting conned). Fear of the inefficiencies of cronyism has led to the stigmatization of nepotism and various regulations to prevent its spread (e.g., a friend of mine recently told me that his father's large international law firm has a total ban on hiring family members).